Projective space

In mathematics a projective space is a set of elements similar to the set P(V) of lines through the origin of a vector space V. The cases when V=R2 or V=R3 are the projective line and the projective plane, respectively.

The idea of a projective space relates to perspective, more precisely to the way an eye or a camera projects a 3D scene to a 2D image. All points which lie on a projection line (i.e. a "line-of-sight"), intersecting with the focal point of the camera, are projected onto a common image point. In this case the vector space is R3 with the camera focal point at the origin and the projective space corresponds to the image points.

Projective spaces can be studied as a separate field in mathematics, but are also used in various applied fields, geometry in particular. Geometric objects, such as points, lines, or planes, can be given a representation as elements in projective spaces based on homogeneous coordinates. As a result, various relations between these objects can be described in a simpler way than is possible without homogeneous coordinates. Furthermore, various statements in geometry can be made more consistent and without exceptions. For example, in the standard geometry for the plane two lines always intersect at a point except when the lines are parallel. In a projective representation of lines and points, however, such an intersection point exists even for parallel lines, and it can be computed in the same way as other intersection points.

Other mathematical fields where projective spaces play a significant role are topology, the theory of Lie groups and algebraic groups, and their representation theories.

Contents |

Introduction

As outlined above, projective space is a geometric object formalizing statements like "Parallel lines intersect at infinity". For concreteness, we will give the construction of the real projective plane RP2 in some detail. There are three equivalent definitions:

- The set of all lines in (real 3-)space R3 passing through the origin (0, 0, 0). Every such line meets the sphere of radius one centered in the origin exactly twice, say in P = (x, y, z) and its antipodal point (-x, -y, -z).

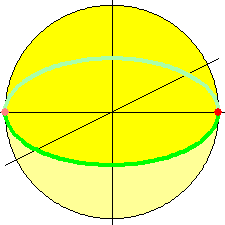

- RP2 can also be described to be the points on the sphere S2, where every point P and its antipodal point are not distinguished. For example, the point (1, 0, 0) (red point in the image) is identified with (-1, 0, 0) (light red point), etc.

- Finally, yet another equivalent definition is the set of equivalence classes of R3\(0, 0, 0), i.e. 3-space without the origin, where two points P = (x, y, z) and Pˈ = (xˈ, yˈ, zˈ) are equivalent iff there is a nonzero real number λ such that P = λ·Pˈ, i.e. x = λxˈ, y = λyˈ, z = λzˈ. The usual way to write an element of the projective plane, i.e. the equivalence class corresponding to an honest point (x, y, z) in R3, is

-

- [x : y : z].

The last formula goes under the name of homogeneous coordinates.

Notice that any point [x : y : z] with z ≠ 0 is equivalent to [x/z : y/z : 1]. So there are two disjoint subsets of the projective plane: that consisting of the points [x : y : z] = [x/z : y/z : 1] for z ≠ 0, and that consisting of the remaining points [x : y : 0]. The latter set can be subdivided similarly into two disjoint subsets, with points [x/y : 1 : 0] and [x : 0 : 0]. In the last case, x is necessarily nonzero, because the origin was not part of RP2. Thus the point is equivalent to [1 : 0 : 0]. Geometrically, the first subset, which is isomorphic (not only as a set, but also as a manifold, as will be seen later) to R2, is in the image the yellow upper hemisphere (without the equator), or equivalently the lower hemisphere. The second subset, isomorphic to R1, corresponds to the green line (without the two marked points), or, again, equivalently the light green line. Finally we have the red point or the equivalent light red point. We thus have a disjoint decomposition

- RP2 = R2 ⊔ R1 ⊔ point.

Intuitively already clear, and made precise below, R1 ⊔ point is itself the real projective line RP1. Considered as a subset of RP2, it is called line at infinity, whereas R2 ⊂ RP2 is called affine plane, i.e. just the usual plane.

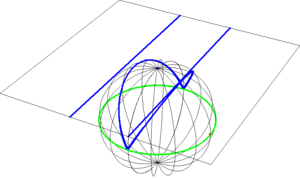

The next objective is to make the saying "parallel lines meet at infinity" precise. A natural bijection between the plane z = 1 (which meets the sphere at the north pole N = (0, 0, 1)) and the affine plane inside the projective plane (i.e. the upper hemisphere) is accomplished by the stereographic projection, i.e. any point P on this plane is mapped to the intersection point of the line through the origin and P and the sphere. Therefore two lines L1 and L2 (blue) in the plane are mapped to what looks like great circles (antipodal points are identified, though). Great circles intersect precisely in two antipodal points, which are identified in the projective plane, i.e. any two lines have exactly one intersection point inside RP2. This phenomenon is axiomatized and studied in projective geometry.

Definition of projective space

Real projective space, RPn, is defined by

- RPn := (Rn+1 \ {0}) / ~,

with the equivalence relation (x0, ..., xn) ~ (λx0, ..., λxn), where λ is an arbitrary non-zero real number. Equivalently, it is the set of all lines in Rn+1 passing through the origin 0 := (0, ..., 0).

Instead of R, one may take any field, or even a division ring, k. Taking the complex numbers or the quaternions, one obtains the complex projective space CPn and quaternionic projective space HPn. In algebraic geometry the usual notation for projective space is Pnk.

If n is one or two, it is also called projective line or projective plane, respectively. The complex projective line is also called the Riemann sphere.

As in the above special case, the notation (so-called homogeneous coordinates) for a point in projective space is

- [x0 : ... : xn].

Slightly more generally, for a vector space V (over some field k, or even more generally a module V over some division ring), P(V) is defined to be (V \ {0}) / ~, where two non-zero vectors v1, v2 in V are equivalent if they differ by a non-zero scalar λ, i.e., v1 = λv2. The vector space need not be finite-dimensional; thus, for example, there is the theory of projective Hilbert spaces.

In the theory of Alexander Grothendieck, especially in the construction of projective bundles, there are reasons for applying the construction outlined above rather to the dual space V*, the reasons being that we would like to associate a projective space to every scheme Y and every quasi-coherent sheaf E over Y, not just the locally free ones. See EGAII, Chap. II, par. 4 for more details.

Projective space as a manifold

The above definition of projective space gives a set. For purposes of differential geometry, which deals with manifolds, it is useful to endow this set with a (real or complex) manifold structure.

Namely consider the following subsets: ![U_i = \{[x_0:\cdots: x_n], x_i \neq 0\}, i=0, \dots,n](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/57ef880c94a79ead72dd44bb272a93e4.png) . By the definition of projective space, their union is the whole projective space. Further, Ui is in bijection to Rn (or Cn) via

. By the definition of projective space, their union is the whole projective space. Further, Ui is in bijection to Rn (or Cn) via

(the hat means that the i-th entry is missing).

The example image shows RP1. (Antipodal points are identified in RP1, though). It is covered by two copies of the real line R, each of which covers the projective line except one point, which is "the" (or a) point at infinity.

We first define a topology on projective space by declaring that these maps shall be homeomorphisms, that is, a subset of Ui is open iff its image under the above isomorphism is an open subset (in the usual sense) of Rn. An arbitrary subset A of RPn is open if all intersections A ∩ Ui are open. This defines a topological space.

The manifold structure is given by the above maps, too.

Another way to think about the projective line is the following: take two copies of the affine line with coordinates x and y, respectively, and glue them together along the subsets x ≠ 0 and y ≠ 0 via the maps

The resulting manifold is the projective line. The charts given by this construction are the same as the ones above. Similar presentations exist for higher-dimensional projective spaces.

The above decomposition in disjoint subsets reads in this generality:

- RPn = Rn ⊔ Rn-1 ⊔

⊔ R1 ⊔ R0,

⊔ R1 ⊔ R0,

this so-called cell-decomposition can be used to calculate the singular cohomology of projective space.

All of the above holds for complex projective space, too. The complex projective line CP1 is an example of a Riemann surface.

The covering by the above open subsets also shows that projective space is an algebraic variety (or scheme), it is covered by n + 1 affine n-spaces. The construction of projective scheme is an instance of the Proj construction.

Projective space and affine space

There are some advantages of the projective space against affine space (e.g. RPn vs. Rn). For these reasons it is important to know when a given manifold or variety is projective, i.e. embeds into (is a closed subset of) projective space. (Very) ample line bundles are designed to tackle this question.

Note that a projective space can be formed by the projectivization of a vector space, as lines through the origin, but cannot be formed from an affine space without a choice of basepoint. That is, affine spaces are open subspaces of projective spaces, which are quotients of vector spaces.

- Projective space is a compact topological space, affine space is not. Therefore, Liouville's theorem applies to show that every holomorphic function on CPn is constant. Another consequence is, for example, that integrating functions or differential forms on Pn does not cause convergence issues.

- On a projective complex manifold X, cohomology groups of coherent sheaves F

- H∗(X, F)

, the zero-th cohomology of the sheaf of holomorphic functions). In the parlance of algebraic geometry, projective space is proper. The above results hold in this context, too.

, the zero-th cohomology of the sheaf of holomorphic functions). In the parlance of algebraic geometry, projective space is proper. The above results hold in this context, too. - For complex projective space, every complex submanifold X ⊂ CPn (i.e., a manifold cut out by holomorphic equations) is necessarily an algebraic variety (i.e., given by polynomial equations). This is Chow's theorem, it allows the direct use of algebraic-geometric methods for these ad hoc analytically defined objects.

- As outlined above, lines in P2 or more generally hyperplanes in Pn always do intersect. This extends to non-linear objects, as well: appropriately defining the degree of an algebraic curve, which is roughly the degree of the polynomials needed to define the curve (see Hilbert polynomial), it is true (over an algebraically closed field k) that any two projective curves C1 and C2 ⊂ Pkn of degree e and f intersect in exactly e·f points, counting them with multiplicities (see Bézout's theorem). This is applied, for example, in defining a group structure on the points of an elliptic curve, like y2 = x3−x+1. The degree of an elliptic curve is 3. Consider the line x = 1, which intersects the curve (inside affine space) exactly twice, namely in (1, 1) and (1, −1). However, inside P2, the projective closure of the curve is given by the homogeneous equation

- y2·z = x3−x·z2+z3,

- Any projective group variety, i.e. a projective variety, whose points form an abstract group, is necessarily an abelian variety, i.e. the group operation is commutative. Elliptic curves are examples for abelian varieties. The commutativity fails for non-projective group varieties, as the example GLn(k) (the general linear group) shows.

Axioms for projective space

A projective space S can be defined abstractly as a set P (the set of points), together with a set L of subsets of P (the set of lines), satisfying these axioms :

- Each two distinct points p and q are in exactly one line.

- Veblen's axiom: If a, b, c, d are distinct points and the lines through ab and cd meet, then so do the lines through ac and bd.

- Any line has at least 3 points on it.

The last axiom eliminates reducible cases that can be written as a disjoint union of projective spaces together with 2-point lines joining any two points in distinct projective spaces. More abstractly, it can be defined as an incidence structure  consisting of a set P of points, a set L of lines, and an incidence relation I stating which points lie on which lines.

consisting of a set P of points, a set L of lines, and an incidence relation I stating which points lie on which lines.

A subspace of the projective space is a subset X, such that any line containing two points of X is a subset of X. The full space and the empty space are subspaces.

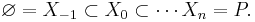

The geometric dimension of the space is said to be n if that is the largest number for which there is a strictly ascending chain of subspaces of this form:

Classification

- Dimension 0 (no lines) The space is a single point.

- Dimension 1 (Exactly one line) All points lie on the unique line.

- Dimension 2 (There are at least 2 lines, and any two lines meet) The definition of a projective space for n = 2 is equivalent with that of a projective plane. These are much harder to classify, as not all of them are isomorphic with a PG(d, K). The Desarguesian planes satisfying Desargues's theorem are projective planes over division rings, but there are many non-Desarguesian planes.

- Dimension at least 3 (There are 2 non-intersecting lines.) Veblen & Young (1965) proved the Veblen-Young theorem that if the dimension n ≥ 3, every projective space is isomorphic with a PG(n, K), the n-dimensional projective space over some division ring K.

There are

projective planes of order 2, 3, 4, …, 10. The numbers beyond this are very hard to calculate.

The smallest projective plane is the Fano plane, PG[2,2] with 7 points and 7 lines.

Morphisms

Injective linear maps T ∈ L(V,W) between two vector spaces V and W over the same field k induce mappings of the corresponding projective spaces via

where v is a non-zero element of V and [...] denotes the equivalence classes of a vector under the defining identification of the respective projective spaces. Since members of the equivalence class differ by a scalar factor, and linear maps preserve scalar factors, this induced map is well-defined. (If T is not injective, it will have a null space larger than {0}; in this case the meaning of the class of T(v) is problematic if v is non-zero and in the null space. In this case one obtains a so-called rational map, see also birational geometry).

Two linear maps S and T in L(V,W) induce the same map between P(V) and P(W) if and only if they differ by a scalar multiple of the identity, that is if T=λS for some λ ≠ 0. Thus if one identifies the scalar multiples of the identity map with the underlying field, the set of k-linear morphisms from P(V) to P(W) is simply P(L(V,W)).

The automorphisms P(V) → P(V) can be described more concretely. (We deal only with automorphisms preserving the base field k). Using the notion of sheaves generated by global sections, it can be shown that any algebraic (not necessarily linear) automorphism has to be linear, i.e. coming from a (linear) automorphism of the vector space V. The latter form the group GL(V). By identifying maps which differ by a scalar, one concludes

- Aut(P(V)) = Aut(V)/k∗ = GL(V)/k∗ =: PGL(V),

the quotient group of GL(V) modulo the matrices which are scalar multiples of the identity. (These matrices form the center of Aut(V)). The groups PGL are called projective linear groups. The automorphisms of the complex projective line CP1 are called Möbius transformations.

Generalizations

- dimension

- The projective space, being the "space" of all one-dimensional linear subspaces of a given vector space V is generalized to Grassmannian manifold, which is parametrizing higher-dimensional subspaces (of some fixed dimension) of V.

- sequence of subspaces

- More generally flag manifold is the space of flags, i.e. chains of linear subspaces of V.

- other subvarieties

- Even more generally, moduli spaces parametrize objects such as elliptic curves of a given kind.

- other rings

- Generalizing to rings (rather than fields) yields inversive ring geometry

- patching

- Patching projective spaces together yields projective space bundles.

Severi-Brauer varieties are algebraic varieties over a field k which become isomorphic to projective spaces after an extension of the base field k.

Projective spaces are special cases of toric varieties. Another generalisation are weighted projective spaces.

See also

Generalizations

- Grassmannian manifold

- Inversive ring geometry

- Space (mathematics)

Projective geometry

- projective transformation

- projective representation

Related

- Geometric algebra

References

- Afanas'ev, V.V. (2001), "projective space", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://eom.springer.de/P/p075350.htm

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998), Projective geometry: from foundations to applications, Cambridge University Press, MR1629468, ISBN 978-0-521-48277-6; 978-0-521-48364-3

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1974), Projective geometry, Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, MR0346652, ISBN 0802021042, OCLC 977732

- Dembowski, P. (1968), Finite geometries, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete, Band 44, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR0233275, ISBN 3540617868

- Greenberg, M.J.; Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries, 2nd ed. Freeman (1980).

- Hartshorne, Robin (1977), Algebraic Geometry, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, MR0463157, ISBN 978-0-387-90244-9, esp. chapters I.2, I.7, II.5, and II.7

- Hilbert, D. and Cohn-Vossen, S.; Geometry and the imagination, 2nd ed. Chelsea (1999).

- Veblen, Oswald; Young, John Wesley (1965), Projective geometry. Vols. 1, 2, Blaisdell Publishing Co. Ginn and Co. New York-Toronto-London, MR0179666 (Reprint of 1910 edition)

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Projective Space" from MathWorld.

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/ProjectiveSpace.html

- Projective Planes of Small Order

![[x_0:\cdots: x_n] \mapsto (\frac{x_0}{x_i}, \dots, \widehat{\frac{x_i}{x_i}}, \dots, \frac{x_n}{x_i})](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/fa0b539d665123340935f6991415b05c.png)

![[y_0:\cdots: y_{i-1}: 1: y_{i+1}: \cdots y_n] \leftarrow (y_0, \dots, \widehat{y_i}, \dots y_n)](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/62067b7bd63c52642dba3dc11e8b131f.png)

![\mathbb P(V) \rightarrow \mathbb P(W), [\mathbf{v}]\mapsto [T(\mathbf{v})],](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/84f2bbb38474ea660f1d05e1fcbb5a74.png)